Suspended spaces#2

Suspended Spaces #02 – A Collective Experience

BlackJack editions

2012

bilingual edition (English / French)

15 x 21 cm (softcover)

272 pages (b/w ill.)

ISBN: 978-2-91806-325-4

EAN: 9782918063254

Contributions by Ziad Antar, Kader Attia, Christian Barani, Stefanie Baumann, François Bellenger, Filip Berte, Denis Briand, Marcel Dinahet, Charlène Dinhut, Marion Hohlfeld, Valérie Jouve, Brent Klinkum, Jan Kopp, Jacinto Lageira, Lia Lapithi, Daniel Lê, Seloua Luste Boulbina, Éléonore de Montesquiou, Françoise Parfait, Mira Sanders, Jad Tabet, Éric Valette, Christophe Viart.

PREFACE

The modus operandi of the Suspended spaces project involves an organic organization which is constructed on the basis of encounters, and is intentionally part and parcel of a collective experiment—and experience—in the making, where movement and displacement are crucial tools.

The first phase of the Suspended spaces project got under way in 2007, in Cyprus. It led us more particularly to develop an interest both in the buffer zone which divides the island in two, and then in the ghost-town-like part of Famagusta, a modern seaside city without its inhabitants since 1974. Based on residencies, we produced some thirty artworks, held exhibitions, organized meetings, screenings and conferences, and published a book, Suspended spaces #1 (in a bilingual French/English version), which describes these various forms of experiments and experiences.

Today, the project is headed towards other horizons and other territories, in Lebanon. Beirut lies not far from Famagusta, on the Mediterranean’s eastern shore; the tales told to us during our stays in Cyprus persuaded us to make the crossing.

The Suspended spaces project, in both its style and its content, defi nes its priorities with regard to its collective evolution and the exchanges it nurtures. To this end, we organized two study days in Rennes and Amiens. During a symposium in Lebanon (three days of exchanges at the invitation of the Beirut Art Center), a ten-day residency was set up between Tripoli, Beirut and Saida. The essence of the contributions in this book resulted from these three periods of exchange.

In the preamble, you will find a little information about the project itself. In fact, it is now possible and necessary for us to outline in detail the Suspended spaces Collective in its ramifi cations and its organic confi guration, and above all affi rm our positions as they have gradually taken shape. We have enjoyed borrowing the form of a manifesto, which functions for us like a shared platform making it possible to consolidate and lay claim to the aesthetic and ethical coherence of our initiatives.

The shift from Cyprus to Lebanon is punctuated by those places that we call “suspended spaces”, whose formal and historical characteristics are particularly elucidated by Françoise Parfait’s essay, which opens the book.

To help with an understanding of the Lebanese political and artistic context, open up different avenues, and provide tools for reflection, other texts have been commissioned.

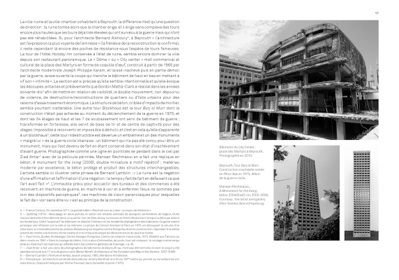

It was important, first and foremost, to let Jad Tabet have his say, for he informed us about the existence of a huge unfi nished fair site designed by Oscar Niemeyer in Tripoli, in northern Lebanon. A stroll in this spectacular architectural work, which is paradoxically both maintained and abandoned, was a powerful moment in our Lebanese residency.

We also felt it important to ask Stefanie Baumann to go back over the emergence of a generation of Lebanese artists, today a major presence in the international art scene, by emphasizing the political and media-related context of the day.

Punctuating this Lebanese suite, Seloua Luste Boulbina compares the issue of suspension, as a posture or stage in philosophical research, with that of hospitality, opened up by displacement to alien land, the shift of the project towards Lebanon in particular, and that of the relationship between guest and host in general.

Among the different lines of thinking that were introduced in the project’s first stage, the matter of the artist’s role was recurrent. The book’s second chapter returns to these confrontations between the artist and reality, History and territory, which are based on the hypothesis of the artist’s singular way of looking at things.

Jacinto Lageira roundly opens up the issue of the role of art by questioning its reparatory capacity, when it takes as its object History’s wounds. The issue is first seen with the distancing of the subject peculiar to philosophical reflection, but in the essay’s second part it is enhanced by an inclusion of this line of thought in the author’s autobiographical context, Portugal and its colonial wars.

This relation to History was the object of many discussions among the various protagonists in our project; some debates were embarked upon in the first book Suspended spaces #1, and Eric Valette focuses on replying to one of them, to do with the question of the knowledge necessary for, or produced by, the artistic approach to a sensitive issue.

As a counterpoint, Denis Briand comes back to a precise artistic example, that of Avi Mograbi, regarded as a case study. The position of the Israeli artist, within a borderline territory (border areas, check points), and of committed stances, proposes an example of a powerful artistic approach that takes place at the crossroads of social, political and aesthetic methods.

The artist Valérie Jouve illustrates one of the forms of artistic research, where perceptible experience, related here through photography, becomes linked with knowledge coming from other fi elds of research, like Edward Saïd’s historical work, Orientalism.

The thinking developed from the Cypriot stage has opened out onto the question of modernism and its failures, with different envisaged spaces in suspense appearing as symptoms. Adaptations, appropriations, and re-appropriations of modernist forms and concepts displaced in time and geographical space seem to be set at the heart of the theoretical evolution of the Suspended spaces project.

As an observer of the development of modernist ideals exported by Europe to Africa, Kader Attia elaborates in his works and refl ections an original viewpoint about the many different exchanges which help to produce and experience architecture. The notions of reparation and re-appropriation are central in his research.

Like Kader Attia, Christophe Viart does not see the modern failure as an object of nostalgia or as a need to wipe the slate clean, but rather as a legacy likely to stir up both poetic ways of looking at things and strong artistic gestures, even in their more damaged forms (the grands ensembles or large complexes).

On another continent and in another economy, Marion Hohlfeldt recalls the existence of modern economic failures also producing spaces in suspense, like the city of Detroit in the United States, completely imploding since the crisis in the automobile industry.

To open rather than wind up this sequence of reflections, Charlène Dinhut comes up with an attempt to define the notion of suspend/suspense associated with space, offering us, hopefully, possible occurrences in art production, past and in the offing alike.

The Suspended spaces project brings together researchers, including artists, who account for the majority of participants. For each work, we have been keen to associate the different areas of research, in one way or another. During the meetings at the Beirut Art Center (May 2011), everyone had their say, for example. But so as not to artifi cially subject artistic research to the rigidity of the passage to the text, we suggested that the artists collaborate in the book in the form of visual and textual interventions, reacting to the exchanges and the stay in Lebanon. These projections encompass notes, observations, forthcoming projects, and avenues of work, be they precise or merely sketched out.

The book ends with a sweeping overview of our past actions and programmes, and our projects to come, a background to the project in the form of a graphic diagram.

Last of all, a selective and subjective bibliography lists the handful of books cluttering our respective desks and work places, which have gone hand-in-hand with our research over many long months.

An international project such as ours cannot skimp on a line of thinking about the issue of language, the one we use to communicate between us, with our hosts, and with people we meet. Our two books have opted for two languages: French, firstly, which is the most obvious shared language of the project’s “pilots”, and English, for other obvious reasons.

This concern with translation does not hide other frustrations: the fact that it was not possible to translate our first book into Greek and Turkish, and the fact that we cannot translate this book into Arabic. If economic restrictions, international practices and our limited language skills have forced us to opt here for just this English translation, we are determined not to let this practice become a “norm” (we had, for example, proposed a simultaneous translation into Arabic of all our papers and communiqués at the Beirut Art Center).

Displacement, the off-centering of the artistic eye, and the return of reality are seen in this project as an attempt to put back into perspective and — why not? —reconcile universalist modernist idealisms and often dramatic geopolitical realities. And in the daily round of this research into displacement, efforts to understand and to be understood are also an important part of the work and the experiments, in a project which we feel more and more passionate about, for its capacity to become the object of narratives.

Suspended spaces # 2